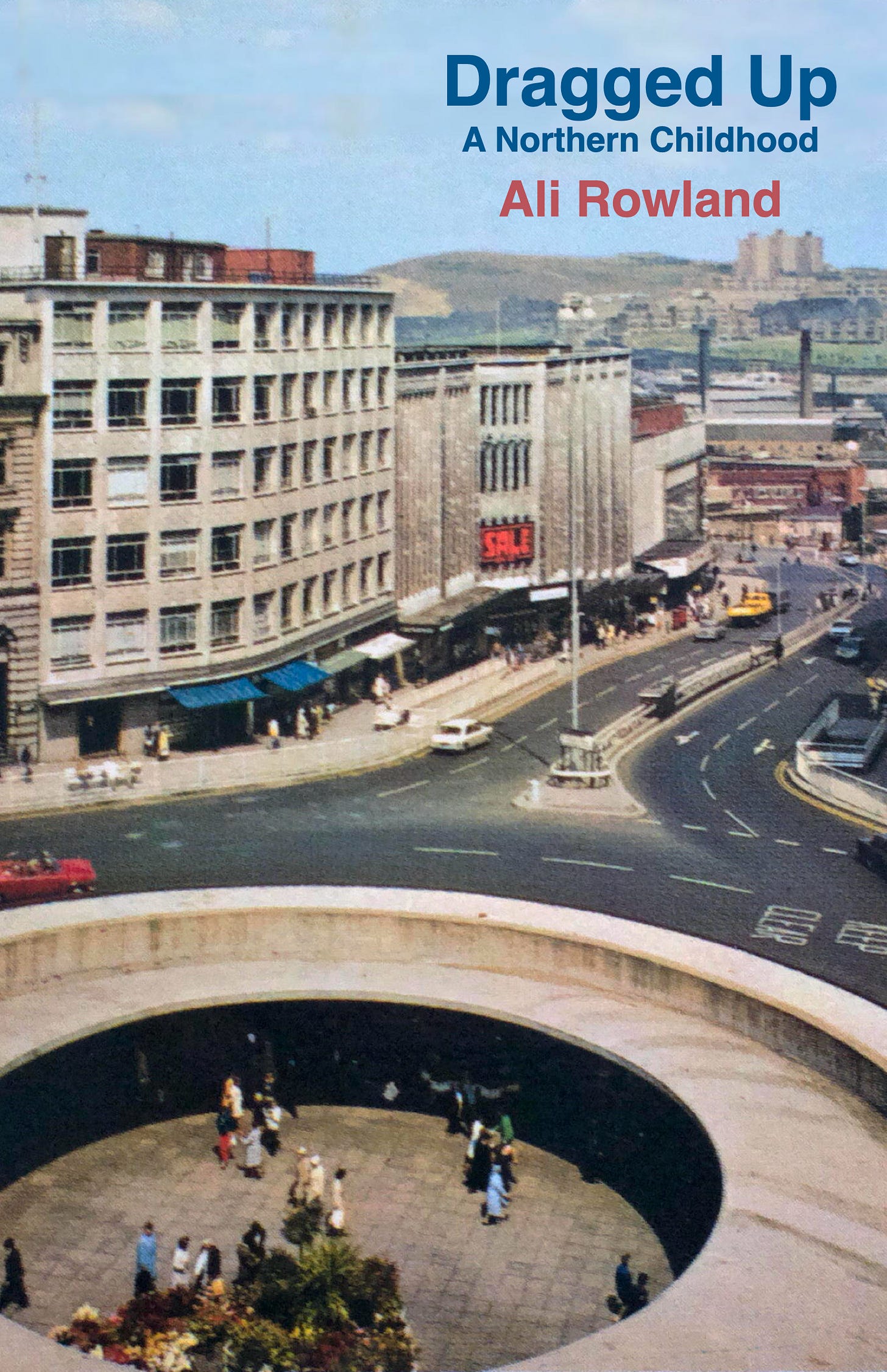

46. Ali Rowland

Sheffield born writer, who now lives in Northumberland, and was recently nominated as a Best of the Net poet. Proudly published by the fledgeling Sixty Odd Press

Ali is a Best of the Net nominated poet from Northumberland The poetry below is a selection of pieces from new collection “Dragged Up - A Northern Childhood” which has been recently published through the 60 Odd Press.

Her first poetry collection “Rooted” was published by Maplestreet Press earlier this year when she was the writer in Residence at the Dovecote Street arts centre in Amble. You can find more of her work at “Musings of a Mad Woman” on Substack.

Poems

Sheffield, The Landscape of the 1970s Lessons From a Bully Weston Park Museum Winds Through the Olive Trees A Flavour of the Seventies No Peter, No

Sheffield, The landscape of the 1970s

There was a hole in the road that was meant to be there, underpasses delivered you into the middle open to the city air and din of buses, their reverb in the ears of sad looking exotic fishes caught behind algea-ing Perspex in the concrete walls. Other key features: seven hills like Rome; a famous factory mass producing liquorice sweets; open-air paddling in the Santorini-blue painted cascade; a snuff mill; the charms of an industrial hamlet; a glittering grey tower of arts; cities in the sky like open concertinas made of folded cardboard boxes; peace gardens; a theatre that could mould our minds. The glorious People’s Republic. <<<

Lessons from a Bully

He was a big, loud, burly man who muffled into his thick, peppercorn beard. It was whispered down the school he’d been a policeman, and that he had a slipper in his cupboard which could be used on miscreant eleven year-olds, a privilege of our age. The first day in his class he showed us ‘my size 9’, a grown-up version of our own slip-on PE shoes. From the start, he liked to share the details of Joe’s crimes with us. One day, the contents of Joe’s desk were in a box outside our classroom door. Teacher told Joe to go round each room until he found someone willing to have him in their class. We listened as we worked to the rhythm of Joe kicking a heavy cardboard box along the orange lacquered wooden floor. Joe was the only black child in our class. There must have been some staffroom agreement that each adult would put pity for Joe from their hearts, for at each door, even kindly Mrs Burton’s, he was told, ‘No.’ Joe, dry eyes cast down, shuffled slower as the day went on. With each thwack the box disintegrated more, as books, pens, the accumulated things of a school boy’s desk, leaked out of its beaten corners, the cardboard cracking along jagged fault lines. There was a book on evolution where someone wrote the teacher’s name next to the picture of early man: both looked hairy, unkempt and stooped a little: we showed it to each other, but it didn’t make us laugh. <<<

Weston Park Museum

Cases buzzed with phosphorescent light in the dark maze of the steel-plate room. following the trail an act of faith, nothing but soft blackness beneath your feet. Exhibits glisten on their inky velvet pillows, tooled or smooth, functional or decorative, polished ‘till the silver glows like gold, a metallic alchemy, a city’s legacy. Being driven past the steel works on a winter afternoon, a gate swings open so I glimpse the orange-hot furnace in its massive shed, everything else made silhouette. Briefly, the image of a muscled, sweating man, shovelling this greedy dragon’s mouth, like a tableau of effort against adversity in a wartime poster. <<<

Winds Through The Olive Trees

One frosty afternoon we rehearsed Christmas songs round the sharp-tuned piano in the hall. The air we brought in from the twilight playground smelled of cold. Cross-legged on the floor, we took turns spinning ourselves dizzy on the slippery layers of lacquer. A faded chalk circle showed where a child had once accidentally peed. We sang of sheep on hillsides, long ago, not like the steep, city streets we knew. These were children’s carols, repetitive phrases, rhymes designed to stick in tender minds, rhythms accompanied with triangles and maracas. I struggled, drawing in my asthma-ed breath, to sing. Soon, I would have lent to me a school recorder in its red, velvet sleeve, the mouthpiece already lightly-teethed. We sang of winds blowing through olives trees, exotic fruits we’d never seen. The tune engaged my heart and, like the angels bending low, the sound brought a gentle peace I didn’t know. <<<

A Flavour of the Seventies

My mum would call my dad a chuff, a word not in the concise dictionary. Now I’ve looked it up I know he didn’t move with a regular, sharp puffing sound, or chamfer the ground like a raging bull. I’d thought it was a bird she didn’t like, but she must have meant slang for dirtbag or bastard— in any case I’m glad that Yorkshire’s long gone where Every mother’s duck’s a swan, Them that’s worth nowt’s never in danger, and I’m up and down like a dog at a fair. It can’t be sweetened with food nostalgia ‘cos he’d bring home each night a quarter of spice, a bag of boiled and sugared gelatine, tooth- breakers, not exotic treats. We ate cheap meats: tripe and tongue and chap - I don’t like to think of the parts of the beasts they came from. I refused to eat the crispy skin-haired edges. Ah, you’ve missed the best bit, you daft girl, it’s that fat that would make your hair curl. <<<

No Peter, No

It is Peter I remember, his rosy, fuzzy, water-coloured cheeks, the same hue as the apples, his neat blond hair. Jane seemed barely there, a shadow, issuing the warnings, incantations. They were anachronistic even then, the gentle fifties trying to impose themselves on the seventies: my first teacher’s mini-dress, her bob, the prevalence of badly-fitting flares. I have to read the books before bed; the apples I don’t care about, my head is tired, my heart drumming on the thought I may not make it to the end, I squirm to stay awake. I think of touching the butterfly sticker on my coat peg; I don’t want to lose it because I can read my name, it being so much prettier than all those dull words said again and again. <<<

If you have enjoyed these poems, please consider supporting Ali and the Sixty Odd Poets project by purchasing a copy of Ali’s collection, Dragged Up - A Northern Childhood

Very familiar. Mr Seddon at 6ft 4 was a dab had at whacking the short learning disabled boy with his classroom ruler. I didn't know the language but I knew it was wrong!

Fabulously retold stories Ali Rowland.

What a glorious set of poems! I'm from that London, but each poem had a resonance. Beautiful.